®

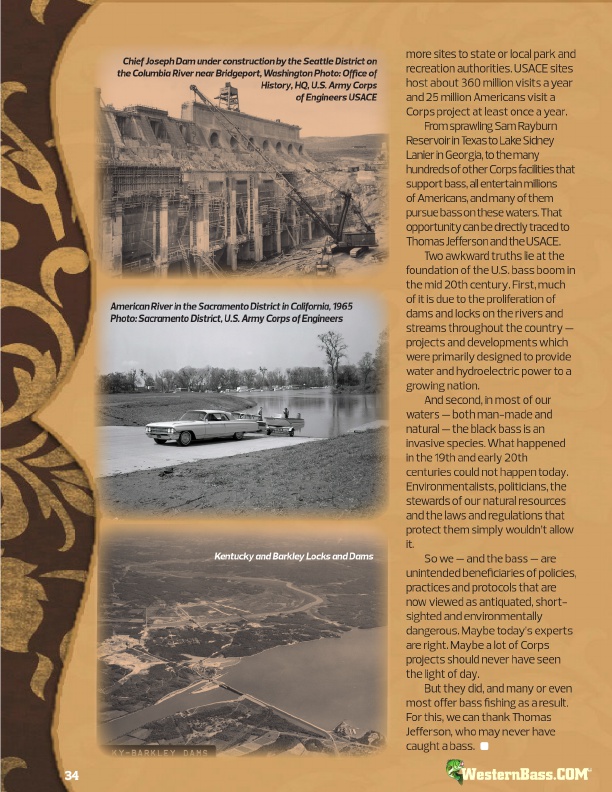

Chief Joseph Dam under construction by the Seattle District on the Columbia River near Bridgeport, Washington Photo: Office of

History, HQ, U.S. Army Corps

of Engineers USACE

American River in the Sacramento District in California, 1965 Photo: Sacramento District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Kentucky and Barkley Locks and Dams

more sites to state or local park and recreation authorities. USACE sites host about 360 million visits a year and 25 million Americans visit a Corps project at least once a year.

From sprawling Sam Rayburn Reservoir in Texas to Lake Sidney Lanier in Georgia, to the many hundreds of other Corps facilities that support bass, all entertain millions of Americans, and many of them pursue bass on these waters. That opportunity can be directly traced to Thomas Jefferson and the USACE.

Two awkward truths lie at the foundation of the U.S. bass boom in the mid 20th century. First, much of it is due to the proliferation of dams and locks on the rivers and streams throughout the country — projects and developments which were primarily designed to provide water and hydroelectric power to a growing nation.

And second, in most of our waters — both man-made and natural — the black bass is an invasive species. What happened in the 19th and early 20th centuries could not happen today. Environmentalists, politicians, the stewards of our natural resources and the laws and regulations that protect them simply wouldn’t allow it.

So we — and the bass — are unintended beneficiaries of policies, practices and protocols that are now viewed as antiquated, short- sighted and environmentally dangerous. Maybe today’s experts are right. Maybe a lot of Corps projects should never have seen the light of day.

But they did, and many or even most offer bass fishing as a result. For this, we can thank Thomas Jefferson, who may never have caught a bass.

34